On Tuesday 8 March, LME nickel futures prices rose to unprecedented levels in what seems to have been a short squeeze. The exchange, confronted with one or more potentially defaulting clearing members, decided to step in and save them. It canceled all trades executed on 8 March, closed the market for an extended period and changed the situation to the benefit of market participants with short positions and the clearing members that might be negatively impacted by these participants not being able to post the required margin. With that, the exchange essentially passed on its problems to the end-clients. To save its members, the LME transferred more than 27 billion dollar from end-clients with long positions to end-clients with short positions. And by doing so, it effectively transformed counterparty risk into market price risk for end-clients with long positions.

Background

The London Metal Exchange (LME) is a long-established futures marketplace founded in 1877, on whose platforms the majority of all global non-ferrous metal futures business is transacted. One of the metals traded on LME is nickel. Demand for this metal has grown in recent years, among others due to its applicability in the production of rechargeable batteries. As such, nickel plays a role in reaching the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. In 2021, the global nickel mine production reached 2.7 million tonnes. The top five nickel producing countries were Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia, New Caledonia and Australia. One futures contract on LME represents 6 tonnes of nickel. During the first months of 2022, total open interest in nickel futures on LME represented roughly 1.3 million tonnes.

Volume & open interest in LME nickel futures

The LME functions comparable to other commodity futures exchanges. Many participants use LME futures contracts to hedge (part of their) market risk. For instance, producers of nickel typically sell futures short to protect the value of their (expected) production. If the nickel price comes down, they make a profit on their futures position, which compensates for the loss in value of their (yet to be produced) nickel. On the flip side, if prices rise, the increase in value of their nickel will be offset by losses on their futures position. Especially when the actual price of nickel is high, hedging can be extremely attractive for producers. By selling more futures contracts the producer can essentially lock in this price for a larger part of its future production. One of these hedgers is the world’s largest nickel producer, the Tsingshan Holding Group.

On the opposite side of these producers, end-users and processors of nickel may buy futures contracts to hedge their future demand. They protect themselves against future price rises and/or aim to benefit longer from price levels they currently perceive as attractive.

But as is typical for futures markets, the hedgers on the long side and on the short side almost never perfectly match. The sizes they are willing to hedge may not match. Or the moment they are willing to hedge may not match. Or, connected to that, the price level at which they are willing to hedge may not match. Therefore, well-functioning futures markets require the participation of speculators. One of their roles is to carry the market risk that other participants are not willing and/or not able to bear. In exchange, they expect to receive a risk premium. In addition, by buying when they believe the actual price is too low and by selling when they believe it is too high, they can offer liquidity and contribute to the price discovery process.

A large producer like Tsingshan, whose short position has remained unclear but was understood to be at least 100,000 tonnes, will surely know that in order to hold such a sizable short position, there must be other participants willing to hold long positions. Which could be speculators. Transtrend, trading on behalf of its clients, was one of these speculators. We had been holding a long position in LME nickel futures for more than a year. Essentially, we trade this market for the same reason that Tsingshan took such a large position in it; we believe that the energy transition is an ongoing trend that will require among others nickel. Tsingshan aims to make money by producing nickel, but for obvious reasons isn’t willing to carry (all of) the market price risk involved. Transtrend took on a part of that risk. And as such, we were the perfect trading partners — exactly what the futures markets are intended for.

Technically, Transtrend and Tsingshan were not each other’s counterparties. In fact, it could well be that we did not trade with each other at all. When trading on a futures exchange, the buyer doesn’t know the identity of the seller. Nor does the buyer transfer money directly to the seller. Futures trades made on an exchange are cleared through a clearing house, which acts as the buyer to all sellers and the seller to all buyers. In order to initiate or maintain a futures position, participants have to post a margin with the clearing house through a broker. If their futures position loses value when the market moves against them, they will be required to post additional margin to bring their margin account up to the required level. And if their futures position increases in value, their margin account will be credited with the accrued profit for that day. That’s the deal. It applies to both holders of long positions and holders of short positions. It applies to both speculators and hedgers. It applies to both small participants and large participants. It’s the basic promise participants make when they make a futures trade on an exchange.

Russia invades Ukraine

On Monday 7 March, the price of the 3-month LME nickel futures contract jumped above 30,000 dollar per tonne — a price level not seen since March 2008. Bloomberg reported:

“As investors began to price in a scenario that sees Russian supplies cut in the world of commodities, nickel’s jump on Monday highlights just how volatile markets can get in the face of uncertainty.

It’s not often that a not-so-macro industrial metal like nickel would make news as much as it has on Monday, but its unique position is a reflection of the market’s nervousness about the latest developments regarding the war, particularly as the U.S. possibly considers banning Russian oil imports. The potential squeeze in supplies in oil risk contagion, as buyers are likely to shun Russian products, even if potential restrictions don’t extend to them, due to lack of clarity.

For the metals space, Russia is a big supplier for many materials. The country was the third largest mining country of nickel after Indonesia and the Philippines in 2020, per the International Nickel Study Group in its 2021 factbook. Russia is also estimated to hold a 17% market share of higher quality Class 1 nickel -- essential for batteries for electric vehicles.”

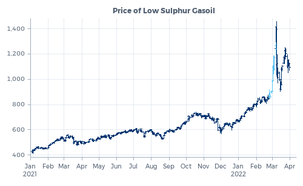

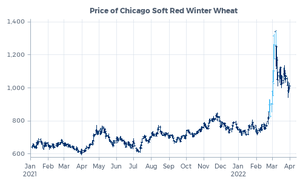

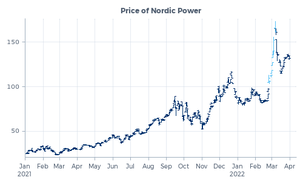

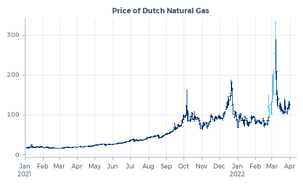

On 7 March, nickel traded 96 percent above the price it traded the day before Russia invaded Ukraine. A strong rise indeed. But not of a magnitude that an experienced commodity trader couldn’t have imagined given the circumstances. And nickel wasn’t the only commodity that rose sharply. Palladium rose 43 percent above its pre-invasion level, European gasoil 46 percent, Chicago soft red winter wheat 60 percent, Nordic power 115 percent, and Rotterdam natural gas a staggering 257 percent! All these markets were — just like nickel — directly or indirectly dependent on exports from Russia and/or Ukraine. In all these markets, participants with short positions were confronted with sizable margin calls. But in none of these markets anything happened like what happened in LME nickel the next day.

The LME claimed that nickel futures traded above their fair value that Monday. To a certain extent, we can agree with that. This was also the case with the other commodities mentioned above. Markets tend to overreact in stressful environments. But if market participants believe a market is trading too high, they should sell. In fact, that’s what we did that Monday in most of these markets. We for instance sold almost half of our long position in nickel futures.

A short squeeze

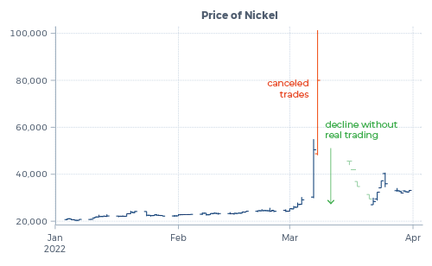

On the morning of Tuesday 8 March, LME nickel rose much higher. It even traded above 100,000 dollar per tonne for a brief moment, before pulling back to find an equilibrium between 79,000 and 84,000 dollar. It continued to trade in that range until the LME decided to halt further trading around 8:15am GMT. Until that moment, approximately 9,000 nickel futures contracts were traded at an average price of around 72,000 dollar. Later that day, the LME announced it had canceled all trades executed on 8 March. We consider this an outrageous measure. We agree that the exchange has the legal right to make such a move, but we cannot reconcile this decision with the principle of well-functioning markets. On the contrary, we believe the decision made by the LME undermines the reliability and the integrity of the exchange. As the Wall Street Journal aptly wrote: “This is moral hazard taken to its extreme.”.

The price explosion did not originate from any new developments regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Instead, stories about a short squeeze played a leading role. One or more participants holding short positions in LME nickel would not be able or willing to transfer the required margin to their brokers. And/or one or more clearing members would not be able or willing to transfer the required margin to the clearing house. Again, it cannot come as a surprise to anyone that when such assertions spread, this could lead to huge price swings. This includes the participants that are the subject of the assertions. And this also includes the exchange. It’s up to the exchange and the regulators to examine what assertions were spread by which participants and with what intentions. If there are signs of market manipulation, these should be addressed. Simply canceling all trades is not the solution, however.

Having said this, let’s not forget that no market ever rises just because of a story. The only real cause of rising prices is the force of participants buying at these high prices, which could be in response to a story. In a free market, no participant is ever forced to buy. Participants may decide to buy, and bear the consequences. Or they may decide not to buy, and bear the consequences. There are a few important ground rules: If you bid a price, you are willing to pay that price. If you don’t bid a price, you won’t have to pay that price.

Which participants could actually have been buying nickel at these high prices on the morning of Tuesday 8 March?

-

Some of these buyers may have been speculators that went long, hoping to profit from an escalating short squeeze. Some of these speculators may have sold later that day, maybe at a higher price, maybe at a lower price. Or maybe the exchange’s decision to halt trading took them by surprise, rendering them unable to liquidate their positions as planned. This type of speculator has been criticized in among others the Chinese media: they would be profiting from the misery of other participants. Indeed, such participants do not really serve the stability of the market. But do their actions qualify as market abuse? That’s up to the exchange to decide. And should the exchange believe they do, it has various measures at its disposal to penalize these participants. Canceling their trades is not one of these measures, however, since it may hurt the other participants in the trades, potentially even more.

-

Other buyers may have been hedgers or speculators that were short nickel futures. These were then facing the risk of having to deposit additional margin — probably more margin than they had anticipated when they entered into their position. By liquidating (part of) their position they would reduce that risk. However, that remains a choice. If they really believed that the actual prices were (way) too high, holding on to their short position and fund it from elsewhere in their portfolio seems like a more reasonable alternative.

-

Yet other buyers may have been clearing members being confronted with clients holding a short position that were not able or willing to deposit the required margin. In such a situation, clearing members are entitled to liquidate (part of) their clients’ positions. However, they don’t have to. And they most certainly don’t have to do so against any price. Again, if they really believed that the actual prices were too high they could have decided to seek funding elsewhere. As a matter of fact, if closing out positions contributes to buying up the market even more above its fair value — resulting in an even higher daily settlement — the margin requirement on the remaining positions increases as well. Clearing members aggressively moving the market away from their positions essentially make things worse, including for themselves.

On the other side of these buyers were the participants who were selling. Some of these sellers may have been hedgers or speculators seizing the opportunity to enter into or add to a short position. Others may have been hedgers or speculators seizing the opportunity to sell out of existing long positions. These sellers did not cause the disruption — they were part of the solution. They did exactly what is required to make a market function. By selling when they believed the prices to be (too) high, they contributed to the price discovery process and added liquidity at the moment it was needed most. Transtrend was one of these sellers. We decided to sell out of our remaining long position in nickel, and we were almost flat when the LME halted further trading.

Price of LME nickel futures ($ per tonne)

Halting trading for a while when prices move past a certain point generally isn’t a bad idea. On various exchanges this is implemented via circuit breakers. In our experience, this tends to calm markets down. However, this typically requires a break of only a few minutes. On the LME, trading in nickel was halted for the rest of the day, and eventually for a six-day period in total. In the meantime, the LME effectively did everything in its power to change the situation to the benefit of only the participants with short positions and the LME clearing members that might be negatively impacted by these participants not being able to post the required margin. When ‘trading’ finally resumed on 16 March, the market immediately went limit-down, rendering any real trading impossible. Real trading resumed on Tuesday 22 March. Participants that had sold their long position on 8 March at prices above 50,000 dollar per tonne, but saw these sales canceled for no valid reason, were ‘offered’ a next opportunity to sell at 27,016 dollar. This represents a loss of 126,372 dollar per contract, compared to the official settlement price on 7 March.

Why did the LME halt trading on 8 March? The picture the LME painted was that there were participants with sizable short positions that would like to size down their positions, but were unable to against fair prices due to the market being disturbed. (You have to read between the lines to see which participants were deemed responsible for the disruption.) The solution the LME came up with was to connect these buyers with willing sellers in a more controlled environment not disrupted by any bad guys. In LME Member Notice 22/055 dated 8 March we read:

“Based on its market engagement, the LME recognizes that market orderliness may be further enhanced by reducing the volume of short positions in the market (and from which participants would be expected to wish to exit as soon as possible on the Resumption Date, with a consequent upward pressure on price).”

This seems like a noble attempt to solve a problem. However, in LME Member Notice 22/057 published two days later we read:

“In relation to netting off long and short positions, the initial responses indicated limited potential uptake, particularly from those with short positions, and considerable differences in view on the appropriate price. However, the LME is continuing to explore this with the market.”

So, the LME halted trading in an attempt to reduce the volume of short positions from which participants would be expected to wish to exit in a more controlled way. And the LME had good reason to believe that at least some of them wished to exit their short position. They expressed that desire by bidding up the price on 8 March. Two days later, however, their desire to buy had vanished. Upon noticing this, there were only two things the LME could have done: immediately reinstate all trades executed on 8 March or perform a mandatory netting-off above Monday’s settlement price for those parties that were actively trading on Tuesday. But the exchange did something else. It just took for granted that the participants that bid and bought aggressively on 8 March ultimately did not want to buy at all. By canceling these trades — i.e., by not holding these participants to their bids — the LME has actively contributed to what may well be the largest spoof in the history of futures trading.

Let’s summarize the impact of the LME’s actions on the various market participants involved:

-

Firstly, the speculators that went long on 8 March, hoping to benefit from an escalating short squeeze. In various media we read that these participants shot themselves in the foot. It’s true they didn’t profit from their transactions. But they didn’t lose any money either. Irrespective of whether they sold higher, lower, or not at all, their net result was zero. All of their trades were canceled.

-

Secondly, we have the buyers on 8 March — presumably mostly hedgers — that were short and liquidated part of their position. By doing so, they essentially contributed to the disruption. On average, they lost 144,000 dollar per contract they bought. But due to the LME’s decision, that loss disappeared. And on top of that, they received 126,372 dollar on every contract they were still short because they ultimately did not buy that day.

-

What about the participants that went short on 8 March? They took a risk and they helped to correct the market by selling against a high price. But even though the market indeed declined to levels way below where they sold, their return was zero.

-

And then we have the participants like Transtrend that were long nickel and sold out of their position on 8 March. On average, they earned 144,000 dollar per contract they sold, but they saw that profit returned to the participants that disrupted the market. And on top of that, they lost 126,372 dollar on every contract they had sold. These are the participants that really got shot in the foot, only not by themselves.

By canceling all trades executed on 8 March, by subsequently closing the market for a longer period of time, and by using that time to try to change the situation to the benefit of the participants with a short position, the LME has effectively transferred roughly 27.4 billion dollar from participants holding long positions to participants holding short positions.

Why did the exchange decide to intervene this massively? To answer this question, we have to go back to the morning of 8 March. The exchange saw itself confronted with one or more clearing members unable or unwilling to transfer the required margin to the clearing house. In other words, one or more potentially defaulting members. But this is something every futures exchange — including the LME — is well prepared for. LME’s Member and Client Default Management Framework document sets out its default waterfall:

LME default waterfall

- First, LME Clear will apply all Collateral provided by the defaulting Member in or towards the discharge of the Default Loss in accordance with the Rules;

- secondly, if the Collateral provided by the defaulting Member is not sufficient to discharge the Default Loss, LME Clear will apply the Default Fund contribution of the defaulting Member in or towards the discharge of the outstanding balance of the Default Loss;

- thirdly, if the Default Fund contribution of the defaulting Member is not sufficient to discharge the balance of the Default Loss, LME Clear will apply its Dedicated Own Resources in or towards the discharge of the outstanding balance of the Default Loss;

- fourthly, if the Dedicated Own Resources of LME Clear are not sufficient to discharge the outstanding balance of the Default Loss, LME Clear will apply the Default Fund contributions of non-defaulting Members either on a pro rata basis or, where an auction has been conducted, in accordance with the juniorisation mechanism set out in Default Procedure Part C6 of the LME Clear Rules in or towards the discharge of the remaining balance of the Default Loss; and

- fifthly, if further resources are required the process will enter the unfunded section, as documented in the LME Clear Recovery Plan.

In short, holders of futures contracts mainly face counterparty risk towards the clearing house and its members. Only after all collateral provided by the members is absorbed, the funds of end-clients are at risk. This has been the foundation of futures markets for more than a century. It is under these conditions that we consider it appropriate to invest our clients’ money in these markets. We wish to participate in the exchange of market price risk. We do not want to be involved in carrying and managing any unnecessary counterparty risk. That’s why we do not trade directly in these markets with other participants, whether it be Tsingshan or some other party, and that’s probably also why they don’t want to trade directly with parties like us.

But what if the clearing members don’t want to live up to their obligations? Normally, this would trigger a default of the member. But the LME found another way out. Instead of letting one or more of its members default, it simply claimed that prices were too high. It canceled all trades executed on 8 March to avoid having to determine a daily settlement price higher than what some of its members were willing to fund. And subsequently, it seems to effectively have manipulated the market price down.

LME’s management feels it saved the exchange. Problem is, it didn’t. It just saved its members from having to deposit billions of dollars’ worth of additional collateral — money that most probably would have been needed for only a few days. With that, the LME essentially passed on its problems to the end-clients. To save its members, the LME transferred more than 27 billion dollar from end-clients with long positions to end-clients with short positions. And by doing so, it effectively transformed counterparty risk into market price risk for end-clients with long positions.

The moment we realized what was really happening, we felt we could no longer entrust the LME with our clients’ money. We had been trading LME futures for more than 30 years, but mid-March we regretfully started to liquidate all of our LME positions. We from time to time held a significant part of the open interest in some of these markets. They offered diversification to our clients’ portfolios, and they offered us a way to meaningfully participate in the energy transition. But when we trade a futures contract, we want to be sure that we primarily exchange market price risk. We wish to actively contribute to the price discovery process and we wish to offer liquidity. But we don’t want an exchange to use our clients’ money to save exchange members that are not being held accountable for their actions.

Our decision to stop trading LME markets isn’t necessarily a final one. We’ve raised our concerns with the exchange. And we hope and expect that other market participants will start up such a dialogue as well, if they haven’t already. Also, it wouldn’t surprise us if the British regulator at some point will knock on their door too. We hope and expect that these discussions will prove fruitful and lead to some serious self-reflection by the exchange, followed up with the necessary improvements to their procedures.

- Source of price, volume and open interest data used in the graphs in this article: Refinitiv, Bloomberg and Transtrend.